The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford has recently called attention to a magnificent ostrich egg cup on Twitter:

#WorldEggDay Silver gilt cup & cover enclosing an ostrich-egg, 46cm tall, made for the prince of Transylvania c. 1576 pic.twitter.com/6Y6ZbA0oem— Ashmolean Museum (@AshmoleanMuseum) October 9, 2015The object is part of the Wellby bequest, which entered the Ashmolean collections in 2012, and has recently been put on a new, permanent display. The objects can be browsed on the website of the museum, where the following information is given about the ostrich egg cup:

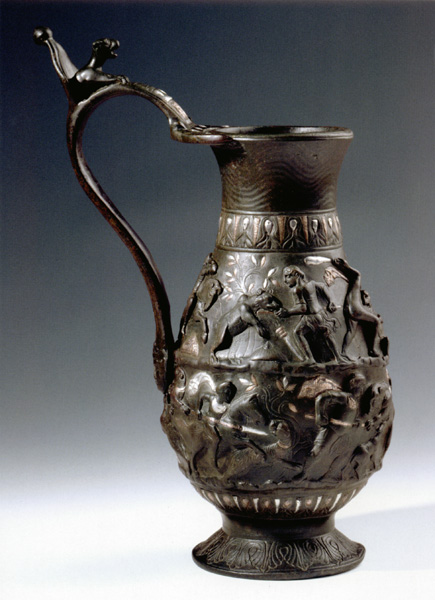

"Silver gilt cup and cover enclosing an ostrich-egg. The body has embossed and enamelled decoration in red, blue, green and white, three vertical straps, surmounted by masks. The cover has three pierced straps enamelled decoration with crosses and fleur-des-lys. The finial is an ostrich-egg holding up a shield with a crowned coat of arms [...] Made for the prince (waivoda) of Transylvania, a member of the Habsburg family, who ruled as a vassel of the Ottoman Empire. The inside of the egg has silver-gilt meticulously decorated with intersecting curving lines. The egg has been replaced or stripped."

The website also gives the insciption around the coat of arms on top of the lid of the cup:

CHRIST BATHORY WAIVODAE. TRANSYLVANIAE. COMITIS SICULORUM 1576

This inscription enables us to identify the owner of the cup more precisely: it was not made for the Prince of Transylvania - who in 1576 was Stephen Báthory - but for his brother, Cristopher (Krisfóf) Báthory.

|

Stephen Báthory, Prince of Transylvania and King of Poland (Giulio Ricci, 1586 - Museum of Applied Arts, Budapest) |

|

| Christopher Báthory |

Kristóf Báthory became the voivod of Transylvania in 1576, when his brother was invited to the throne of Poland. The voivod is a medieval title, it was used to designate the governor of Transylvania, a direct subordinate of the King of Hungary. Since the mid-16th century, Transylvania became an independent state, a vassalage of the Ottoman Turkish Empire, ruled by the Prince of Transylvania. Stephen Báthory was elected prince of Transylvania in 1571 - a title he kept even after he became the King of Poland in 1576. As he spent most of his time in Kraków from then on, he designated his brother, Kristóf as governor (voivod) of Transylvania, and also the count of the Szekler (comes Siculorum). When Kristóf died in 1581, he was succeeded by his son Sigismund Báthory (after the death of Stephen Báthory in 1586, Sigismund became the next Prince of Transylvania). So the ostrich egg cup can be connected with Kristóf Báthory, voivod of Transylvania, and was most likely made at the time when he was elevated to this position.

The coat of arms displayed in the shield on top of the object is the traditional family insignia of the Báthory-family, consisting of three dragon-teeth.

The ostrich egg cup of Christopher Báthory was likely made in Nuremberg, and is a prime example of the curiosity objects popular in the 16th century. I was not aware of it before, and apparently it's existence was not mentioned in Hungarian literature that much either. The fact that it entered the Ashmolean Museum will certainly mean that the object will be the subject of further study and publications in the future. Describing and identifying the hundreds of pieces in the Wellby bequest will naturally take time, as the disclaimer on the Ashmolean website states: "The Museum is planning an extensive programme of scientific and other research on the collection." I hope that the information provided above will soon find its way into the official description of the object as well.

UPDATE: In the meantime, I received a publication of the Ashmolean Museum dedicated to the Michael Wellby Bequest. Written by Timothy Wilson and Matthew Winterbottom, the book includes a selection of objects from the collection, including the Báthory-cup. In the catalogue entry (cat. 14), Christopher Báthory is correctly identified as the putative owner of the object - however, the enty also raises the possibility that the inscription may be a 19th century addition.

Publication details: Timothy Wilson & Matthew Winterbottom: Treasures of the Goldsmith's Art: The Michael Wellby Bequest to the Ashmolean Museum. Oxford, 2015.

UPDATE: In the meantime, I received a publication of the Ashmolean Museum dedicated to the Michael Wellby Bequest. Written by Timothy Wilson and Matthew Winterbottom, the book includes a selection of objects from the collection, including the Báthory-cup. In the catalogue entry (cat. 14), Christopher Báthory is correctly identified as the putative owner of the object - however, the enty also raises the possibility that the inscription may be a 19th century addition.

Publication details: Timothy Wilson & Matthew Winterbottom: Treasures of the Goldsmith's Art: The Michael Wellby Bequest to the Ashmolean Museum. Oxford, 2015.

|

| Ostrich egg cup of Christopher Báthory, 1576. Ashmolean Museum, WA2013.1.128 Photo: Ashmolean Museum, Oxford |